David Lunt, Father, Fisherman, and Maine Coast Icon, Dies at 86

- deanlunt1966

- Feb 14, 2025

- 16 min read

Updated: Feb 27, 2025

David L. Lunt, a lobsterman, entrepreneur, patriarch, optimist, and lover of the open road who rose from humble beginnings to become an iconic coastal figure and powerful voice for Frenchboro—the remote island fishing village where generations of his family worked the sea—died January 8, 2025. He was 86.

Lunt was born and raised on a Maine island still mired in post-Depression poverty and lacking basic conveniences such as running water, electric lights, and telephone service, but he worked tirelessly to pull his community into the modern era, while also pushing forward with progressive ideas in a constant battle to keep it alive. He took a leading role in every island action and decision for the better part of five decades, famously relying on gut instincts and an unflappable demeanor to get things done.

Peter Ralston, renowned coastal photographer and co-founder of The Island Institute, summed up Lunt’s legacy simply: “He was one of the Maine coast’s greats.”

Lunt was just sixty-two-years-old and at the height of his powers in October 2000 when he suffered a massive early morning stroke on Frenchboro, eight miles at sea. Following a tense ride lying on the platform of Starburst, his oldest son’s lobster boat, the crew in a waiting ambulance saved his life, but the stroke left him temporarily paralyzed—unable to walk, speak, or even swallow. He dedicated himself rehabilitation work, and in the following months he regained some strength, fine motor skills, and cognitive abilities, but never enough to go fishing full-time, drive a car down the highway, or bound up and down the flights of stairs running from his wharf to the house. True to his character, he never complained. He reimagined or abandoned some of his dreams, retooled his ambitions, and embarked on a slower, more subdued second act—accepting more help, navigating instead of driving, puttering around the yard, enjoying his role as grandfather, helping at Lunt’s Dockside Deli, and serving as unofficial island elder and ambassador.

“He endured personal trials with fortitude, mostly sitting quietly through the ordeals of his later years,” said Jill Goldthwait, a nurse, former state senator who represented his district and is a board member of the Maine Seacoast Mission. “When he was brought low by a stroke, I slipped into his hospital room and spoke to him. He did not reply, but raised a forearm from the bed and spread his fingers. I dared to slip my hand in his. That hand that had hauled so many traps wrapped securely around mine. There could have been no greater gift.”

Born a Sixth Generation Islander

David Lawrence Lunt was born May 18, 1938, the only child of Sanford L. Lunt and Vivian (Davis) Lunt, and raised on what was known as Outer Long Island or Long Island Plantation. His ancestors, led by Revolutionary War soldier Abner Coffin Lunt, set ashore at Pretty Marsh in 1789 and began farming the land of Mount Desert Island and fishing the waters of Blue Hill Bay. Members of the Lunt family soon worked their way out to Long Island and began building a resilient island community.

David Lunt was a sixth generation islander whose parents grew up in abject rural poverty, an entrenched problem on the outer islands. Sanford “Dick” Lunt, the oldest son in a large clan, dropped out of school at fourteen to work full-time supporting his parents and siblings and then he just never stopped working—ever. A few hundred yards down the road from Dick’s home, Vivian Davis was born on a fish wharf, the eldest daughter of a fisherman and occasional mail carrier. Her family was also poor and she worked relentlessly to escape from it. She spent several years with an aunt, but returned to her childhood home to comfort and care for her mother, who was in her late forties and slowly, painfully dying of cancer. Dick and Vivian married in 1936 and through hard work, determination, and discipline became island icons, helping lead the community for decades.

David Lunt spent his childhood living in a former out building that his parents converted into a modest two-bedroom home on a hillside surrounded by scores of cousins and generations of family members. The island still lacked basic amenities, so as a substitute for electricity, his father and his uncle, Cecil, installed a bank of 56 two-volt batteries on a family wharf and strung enough wire to connect three houses. The bank of batteries, which took six hours to recharge, allowed the families to light a few electric lights after the sun set and watch an hour or two of television each evening. The last person awake, often David, trudged back down to the wharf to shut down the system. Other childhood chores, frequently tied to lack of basics, included emptying family chamber pots and hauling water from a hand-dug well. As a teenager in the 1950s, he installed the island’s first rudimentary telephone system. He acquired a telephone line and telephones from Bartlett’s Island, where family members worked as caretakers, and ran the wire under mud flats, across bare ground, and through trees to connect ten houses. His “party line” system remained in use until a modern local telephone system was installed in 1973.

Lunt attended the island’s one-room K-8 elementary school where all grades were taught by a single teacher who, in most cases, operated as a so-called teacher-preacher—meaning she taught school lessons on weekdays and Bible lessons on Sundays. Lunt, a top student, skipped one grade, and started high school at Higgins Classical Institute, a boarding school in Charleston, as a thirteen-year-old. He later admitted he was too young, especially from a social standpoint. Regardless, he excelled academically and played three sports, although baseball was his best and his favorite. His family closely followed both the old Boston Braves—he often repeated the team's famous 1948 rallying cry, "Spahn and Sain and pray for rain"—and the Boston Red Sox, who fielded his favorite players, Ted Williams and Johnny Pesky. For decades, Red Sox radio play-by-play provided the soundtrack to the island's spring and summer days and the starting point for thousands of conversations.

Lunt graduated in 1955, but with fishing poor and money scarce, he and some cousins headed south to Connecticut looking for work, which they found in East Hartford, making jet engines at the Pratt & Whitney factory—it was the only time he ever collected a weekly paycheck.

Within a year, Lunt returned from the Nutmeg State and bought his dream car—a blue and white 1957 Chevrolet Bel Air hardtop. The car helped him catch the eye of Avis Sandra “Sandi” Morris, a lovely young woman in Bernard who chose to ignore stern family warnings that she and her friends “watch out for those Long Island boys.” Lunt, a cocky, quick-talking young man, cut such a dashing figure that when he rolled into town Sandi said she was “helpless, just helpless.” The couple got married in June 1958 at the Tremont Congregational Church. After a honeymoon on Prince Edward Island, they moved to Frenchboro, living with David’s parents while building their own house overlooking Lunt Harbor. The couple eventually raised three sons, David W., Daniel L., and Dean L., in the home and lived in it for more than sixty years.

While work and raising children dominated the 1960s and 1970s, the couple's R&R breaks included summer picnics on the back shore or a neighboring island, bonfires and skating parties, snowmobiling, card games such as hearts and spades, and television shows such as Hee Haw, Carol Burnett, and Gunsmoke (although any western would suffice). Lunt was such an anti-smoker that after hosting an island card party, he dashed about the house spraying Lysol to cover up the cigarette smoke. Like Dick and Vivian, David and Sandi were also committed non-drinkers. It was Vivian who said the choice was easy after watching so many island relatives privately and publicly battle against alcoholism; and sometimes lose.

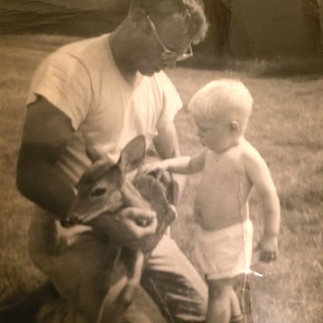

Lunt was a progressive father, especially for a fisherman of his era, tending out to his children, and rarely, if ever, raising his voice. He set aside time for family vacations and special events. In the 1970s, he helped his oldest son, Davie, build his first boat, Starburst. And when his youngest son, Dean, wanted to play Little League baseball, he became assistant coach and ended his fishing days early so that they could race across eight miles of the Atlantic Ocean to Bass Harbor for practices and games. Eventually, David Lunt became one of those handful of dads who sat in folding chairs down the third base line at every one of his son's away summer league and high school baseball games. In his later years, the Lunt house became a common gathering spot for grandchildren and their summer friends, especially after David installed an above ground swimming pool and a trampoline for them to use at will.

A Lifelong Fisherman

David Lunt began fishing when he was about ten-years-old. He worked seining with his father to catch herring, but given lingering island poverty and overall poor fishing, they fished for whatever they could catch to make money, including lobsters or hand-lining for cod off Mount Desert Rock.

“In those days, you had to do multiple things to make a living,” he once said. “There was just never enough money to survive doing only one kind of fishing. When lobsters would drop off, you would start to catch herring, and when they dropped off, you might catch hake and halibut, and then something else. You worked every day to make enough money to live and when not fishing you hunted for food so you could eat.”

As a pre-teen, he began fishing for lobsters in a thirteen-foot skiff sporting a twenty-five-horsepower Johnson outboard; something he continued even after starting a family. His minimalist lobster buoys were marked by an orange spindle and black butt—he didn't want to paint a colored band—to match the colors of his father’s buoys. By doing so, he saved money on paint and minimized the time required to paint them. In the 1960s, Lunt built his first lobster boat, which featured a twenty-two-foot hull that he and his father finished off in the famed Bass Harbor boat shop of his great uncle, Granville “Sim” Davis. David Lunt fished from that small lobster boat every summer and then rejoined his father aboard the David & Vivian when fall weather turned nasty. Not until the late 1970s when he reached his forties, did he own a true year-round boat, Sandi, which featured a 33-foot Young Brothers hull.

One early afternoon while hauling lobster traps alone, a rope tied to a trap that he had just thrown overboard grabbed his ankle and yanked him to the deck. Ever the cool customer, Lunt, in his fifties at the time, wedged himself under the stern while the boat, in gear moving forward, and the trap, underwater serving as a drag, kept the rope taut and seemingly conspired to drag him overboard. Luckily, Lunt remembered the small pair of fingernail clippers he kept in his pant’s pocket. He dug them out and, fiber by fiber, cut his way to freedom. Of course, once free, he got up off the deck and just continued hauling his traps.

While Lunt liked lobster fishing, he never truly loved lobster fishing. He was an ambitious soul and always working on ideas and extra projects, for example spending time designing and trying to patent new fishing tools. By the 1970s, he ran Lunt & Lunt Lobster Company, the small lobster buying business that his parents started in 1951, and managed Lobsterman’s Lunch, a summer-only take-out restaurant on the family wharf. Lobsterman's Lunch was likely the first twentieth century island business to actively market to and welcome guests, boaters, and non-island fishermen to a harbor that historically was considered unfriendly to outsiders. He knew the island needed to escape its own isolation.

Lunt saw his businesses not only as a way to earn extra money, but as a way to support the family, other fisherman, and the community—all of which he fiercely protected. For many years, Lunt & Lunt sold propane, diesel fuel, gasoline, and home heating fuel as a community service, almost always at an overall financial loss. Once he was established, he, like his father, co-signed loans or vouched for a fisherman so they could get they needed to fish or live; whether it was buying an engine or lobster traps or a boat or a house. He effectively seeded the local economy and the community by making it easier for people to remain islanders. During tough winters, Lunt & Lunt sometimes covered health insurance payments and carried unpaid winter fuel bills on the books until spring fishing. Vivian, who handled the books, sweated out the bank account every winter, while David assured her that everything would turn out just fine.

“I could go on and on about my grandfather,” said Zachary D. Lunt, a lobsterman and eighth-generational islander. “He always went to bat for just about anyone out there to get them what they needed or help them find a way so they got what they needed. He was always taking care of people; just a wonderful man. He was the foundation of a family and a community.”

As he matured, David Lunt took swings at bigger and bigger ideas and projects. In the 1980s, he teamed with a Manhattan-based partner to launch Frenchboro Island Seafood Company, an island-based business that made four Lobster-based pasta sauces. The sauces, which included Lobster Saffron and Lobster Curry, included the meat from one full lobster, various other fresh ingredients, and no preservatives. The sauce was packed in canning jars and sold at stores in Maine, such as Save E-Z in Ellsworth, and beyond, such as Macy's and Bloomingdale's. Lunt believed a year-round production facility on Frenchboro would diversify the economy by providing non-fishing jobs to islanders, especially women who had few options. Such opportunities, he felt, made the island more attractive to families, benefitting both the struggling school and the general population. When it started, Frenchboro Island Seafoods employed seven islanders and Lunt said his goal was fifteen. Lunt and another business partner also acquired a warehouse and distribution site on Mount Desert Island.

The challenge, which proved the product’s undoing at a time when such fresh products were less common, was shelf life. Although Frenchboro Island Seafood Co., was relatively short-lived, the sauces and the story made a splash receiving a positive mention in The New York Times. As a result, in 1986, Lunt spent two spring days at Bloomingdale’s in New York City politely answering a wide-range of questions about island life in a Maine accent so thick Manhattanites struggled to understand him. Meanwhile, a local chef served the sauces to delighted store customers. Organizers suggested Lunt don a yellow slicker and stereotypical rain hat to create a “Maine fishing atmosphere” for the event. He just smiled and said, “Nah, I think I’ll pass.”

“I learned so much by watching my father, and questioning him on long car rides,” said Dean L. Lunt, his youngest son. “He felt you should never be afraid of making a decision or failing. If you try something, give it your best shot, and if it doesn’t work out, just forget about it, and try something else. My father was brilliant at moving on. David Lunt never wallowed.”

Frenchboro Teetering on the Edge

Given his family's long history on the coast, Lunt was keenly aware that hundreds of Maine island communities had withered and died during the twentieth century and he relentlessly worked trying to help his hometown—which regularly teetered on the edge—avoid a similar fate. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, school enrollment sometimes dwindled to one pupil while the island's year-round population, once about two hundred strong, had dipped below fifty. Even though, he was a deep-rooted traditionalist and wary of outsiders telling islanders what to do, he never fear necessary change and understood his community's survival in an increasingly complex, costly, and interconnected world require help.

Lunt worked closely with numerous state and federal agencies, and served on several boards and committees lending an authentic voice and guidance to nonprofit organizations, including The Island Institute, Acadia National Park, Maine Coast Heritage Trust, Maine Seacoast Mission, and others.

According to Goldthwait, a key to understanding the calm and quiet (“I never saw him angry”) David Lunt was to observe. “Most of my relationships while I was in office involved a lot of talking,” Goldthwait said. “Not with David. You were not about to get a tutorial about Frenchboro from him, but if you watched and listened, you might get an inkling as to what might be doable.”

One place he sought help was at the fledgling Island Institute. The Institute's co-founders Peter Ralston and Philip Conkling had previously come to Frenchboro to pay him a visit and ask for his support.

“It’s not always easy to ask for help, especially off-island help, but David put community needs above all else; he reached out and over the course of the following decade or so we became great collaborators and friends,” said Ralston. “By example, David taught us a great deal about real leadership and, in the process, about earned respect. He later joined the Island Institute board, and, in that capacity, many others along Maine’s coast and archipelago similarly learned a great deal from him.“

One of their creative and ground-breaking collaborations was the so-called Homesteading Project, intended to create new affordable and market-rate housing and draw new residents who would apply to be part of the program. Lunt led the new Frenchboro Future Development Corp., a private corporation which managed the project. The FFDC worked with a private landowner to obtain nearly fifty acres of land near the harbor, and worked with private and public organizations, such as the Maine Housing Authority, to obtain grants and financing to build houses. Meanwhile, a federal grant covered roads, septic tanks, and wells. Because federal money was involved, a percentage of the houses needed to be considered affordable housing. The Homesteading Project received international publicity and more than 1,000 inquiries in the first month or so. Each applicant was required to demonstrate how they could support themselves and what skills they offered the greater community. Lunt, and others, appeared everywhere from local television to Good Morning America to The New York Times to tell the story of Frenchboro. While Lunt tried to paint a realistic picture of life eight miles at sea, the infamous tabloid newspaper The Star, didn't help his efforts when it headlined its own story: “Come Live With us on Fantasy Island.” While the project evolved, it immediately reinvigorated the school and island population.

In 2000, a handful of months before suffering a stroke, Lunt played a lead role in helping a coalition of organizations raise nearly three million dollars to purchase about 900 acres of undeveloped island land, including 5.5 miles of shore frontage, to protect and preserve it. That land, later combined with additional land, became The Frenchboro Preserve managed by The Maine Coast Heritage Trust.

By the time Lunt, Conkling of The Island Institute, Gary DeLong of the Maine Seacoast Mission, and Jay Espy of the Maine Coast Heritage Trust, gathered in Augusta to receive formal accolades from Gov. Angus King, Lunt, if he chose to do so, could reflect on two decades or so of hard work that had transformed Frenchboro. In that time, Lunt led or was critical to efforts that: dredged Lunt Harbor, refurbished aging island houses, changed Frenchboro from a plantation to a town, built a community center, fire station and fire pond, capped the open dump, protected and conserved 1,000 acres of land, established ongoing funding for historic island buildings, bolstered the island and school population, added to the island's housing stock, replaced the island’s aging power cable, refurbished the island ferry pier, built a town wharf, established off-island telephone service, and, helped build a new island museum and library. On a personal basis, he expanded the family businesses and took a big swing at securing the island's future with Frenchboro Island Seaford Co. If he looked back even longer, you could add ferry service, the Frenchboro Lobster Festival and so much more to the list.

“When one takes on the mantle of ‘Island Patriarch,’ which David did when his father, Sanford, died, it seems you are expected to shoulder the weight of ensuring your community, especially a tiny island community, is treated fairly and not overlooked. David embraced that responsibility,” said Dennis Damon, a former state senator and school teacher who is active in many coastal organizations. “He was the constant voice in the room advocating for Frenchboro. His passing leaves a hole in the community that actually has weight.”

Nothing Like the Open Road

Despite his love of Frenchboro, little doubt existed that Lunt was happiest when riding in a car, truck, or camper on backroads and highways; CDs featuring Rock ‘n Roll legends such as Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly mixed with country favorites such as Hank Williams Sr., Lefty Frizzell, and Ernest Tubb stacked by his side. He just loved the road life. When passing quiet days at campsites from Newfoundland to Mexico, he might read Louis L'Amour novels or play cribbage with fellow campers. And on most warm evenings he slowlyt wandered past campsites scouting for Maine license plates to strike up a conversation with a friendly home state face.

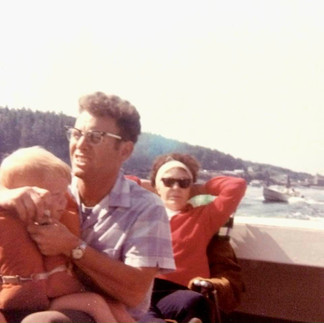

He began such big adventures as a young man when he drove his family from Maine to San Francisco to Seattle and back in six weeks, staying at campgrounds, visiting dozens and dozens of tourist attractions from Yellowstone National Park to San Francisco's Fisherman's Wharf to the Seattle Space Needle to Mount Rushmore. And he never spent two nights in the same place. His oldest sons slept in the back of a Ford station wagon while his youngest slept in the family's tiny pop-up camper. Many mornings David Lunt woke before dawn, bundled up Dean like a sack of potatoes and tossed him in with the others, broke down the site, and was rolling down the road as the sun rose on a new day of adventure.

Family road trips in the 1970s and 1980s included such places as Chesapeake Bay, Nashville, New Orleans, Orlando, and Prince Edward Island. In 1988, he bought a fifth-wheel camper and seriously began traveling America; spending one to three months away. At one point, he and Sandi didn't miss a winter one the road for more than thirty years. Nearly every trip essentially began and ended in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina where he especially loved Myrtle Beach State Park. He felt a month or two each winter was great, but his real dream was becoming a full-time RVer and just living on the road year-round and he began actively planning for those days.

“Dad loved to travel; he loved to just drive and explore. He had an incredible ability to disconnect. He never worried nor cared about getting lost and he never worried much about time,” Dean Lunt said. “He figured if he got lost, he would just see different things and find his way back. He just loved the adventure of it all. Missing a turn or getting lost drove my mother absolutely crazy, but he was so laid back and even-keeled that nothing seemed to bother him.”

The long-term effects of his stroke eventually combined with the couple’s advancing dementia to officially end their days of travel. Living on the road full-time just was never meant to be. He took his final camping trip to Myrtle Beach State Park in the winter of 2019, just a year before the COVID pandemic. In the years following his stroke, he regularly downsized campers so that Sandi could drive them, eventually working his way down to a small truck camper. In the final years, the couple relinquished all planning, logistics and long-distance driving to their youngest son. Regardless of what control he gave up, Lunt never bemoaned his fate or new role, instead he enjoyed what life gave him and understood sacrifices were necessary to squeeze out a few more years of Carolina sunsets.

“My dad refused to complain or engage in what-ifs,” said Dean Lunt. “In the countless hours I spent with him, he never once complained about his stroke; he never once complained when I was in the driver’s seat; he never once raged about the indignities of dementia, even when he could no longer shower or shave himself and could barely walk. He might spend thirty minutes patiently trying to button his shirt without uttering a word. Even when it came time for him to wear a bib to eat, he just let us snap it around his neck so he could dig in. He was such a remarkable and fascinating man in so many ways.”

Finally, as mobility issues and dementia neared a tipping point, and his days on Frenchboro dwindled, he spent as many island afternoons as possible sitting on his Frenchboro deck napping or gazing out over a harbor that had provided the lifeblood of his existence. Most days, he sat with Sandi maybe eating ice cream, binoculars usually at the ready, and always waving to any passersby.

Comments